Penang has often been called a food-lover’s paradise and it’s not hard to see why. Even in a region famed for its street food, this Malaysian island stands out for the staggering quality and variety of options.

In recent years, George Town, the island’s capital, has developed a fine dining scene that can hold its own against larger Southeast Asian metropolises. Nevertheless, one of the joys here is that some of the most phenomenal food can still be found on the street.

Penang’s hawkers are truly legendary; ask a group of locals where to find the best char kway teow or asam laksa and you’re guaranteed to hear impassioned arguments for all sorts of different spots.

From slow-simmered curries to sumptuous noodle soups, the options are hard to beat. Start your day with a white coffee and a thick slice of toast spread with kaya (fragrant pandan custard made with coconut milk) at a kopitiam (local coffee shop), then set off in search of hawker fare.

Here are some of the most exciting examples of Penang food to seek out.

Char Kway Teow

Char kway teow

Even on an island with such an abundance of street food, char kway teow has a special place in the hearts of Malaysians. Savory, rich, gently spicy, and supremely addictive, this noodle stir-fry can be found at virtually every cluster of hawkers in George Town.

At its most elemental, this Southeast Asian dish consists of thick, toothsome rice noodles with garlic, bean sprouts, slices of lap cheong (a sweet, dried Chinese sausage), Chinese chives, scrambled egg, and heaps of seafood often including cockles, prawns, or squid. Some vendors add in crispy lardons or chunks of fishcake for extra umami.

Char kway teow

While the exact ratios and recipes behind each hawker’s sauce vary, most versions include chili jam, a combination of dark and light soy sauce, and occasionally, oyster sauce.

The key to overall flavor profile is something the Cantonese refer to as wok hei, the unmistakable smoky char created by a live fire and a blazing-hot wok.

No one knows exactly who first invented char kway teow, but the dish has its roots among Malaysia’s Teochew community.

Fishermen looking to make a little extra money in the nation’s port towns began serving up the catch of the day to local laborers. At some point, this Penang food classic was born.

Today, char kway teow can be found around Singapore, Malaysia, and farther afield, but many agree the best iterations of the dish still reside in Penang.

Read: Best Places to Visit in Southeast Asia

Asam Laksa

Asam laksa

Equally famous and fiercely beloved among connoisseurs of Malaysian cuisine is asam laksa, an intensely complex noodle soup. Like char kway teow, a bowl of asam laksa incorporates an intricate balance of sweet, spicy, sour, and savory flavors.

The dish has its roots in Malaysia’s Peranakan community. Also known as Straits Chinese or Baba-Nonya, this group of seafaring merchants settled down around key trading ports and routes in Southeast Asia. Their culinary and cultural influence can still be seen from Singapore to Phuket to Malacca.

Asam laksa

A proper asam laksa starts with a rich, flavorful fish stock, then gains depth from a spice paste heady with chilis, belacan (dried shrimp paste), lemongrass, turmeric, shallots, galangal, and other seasonings. Asam means tamarind in Malay and the sticky-sweet pulp adds a pleasant tartness, oftentimes in combination with calamansi lime.

The final flourish is an impressive array of garnishes, often meticulously arranged on a platter. Everything from minced bird’s eye chilis to pineapple or fresh herbs can add pops of color and texture to the finished soup.

Tau Sar Piah

Tau sar piah

Locals in Penang have a serious sweet tooth, as anyone who has wandered past the array of tempting confections in George Town’s Little India will attest. Among the most popular signature treats of the island are these bite-sized morsels.

Tar sar piah consists of sweet mung bean paste wrapped in a flaky pastry rich with butter, lard, or shortening. Brushed with egg yolk for a glossy shine and sprinkled with sesame seeds, they’re an immensely satisfying snack. Originally a Teochew staple, tar sar piah are now enjoyed by just about everyone in Penang.

Nasi Kandar

Nasi kandar

Among Penang’s Tamil Muslim diaspora, this humble working-class staple still holds a special place of honor.

“Nasi” means “rice” in Malay and at its most elemental, nasi kandar means steamed rice with an assortment of hearty curries. While that may sound simple, the nuance found in these slow-braised meats and stews is truly astonishing.

Although the curries may draw heavily on Indian cuisine, nasi kandar is very much a specialty of Penang. During British colonial rule, the dish became all but ubiquitous as a filling lunch option for laborers around George Town’s docks.

To this day, nasi kandar vendors still provide fortifying, home-cooked meals.

Hawker in Penang

Every nasi kandar vendor on the island is different. Some may offer a modest selection of three or four curries, while others ladle out feasts with 30 or 40 options. Expect a mixture of vegetarian curries, often based on eggplant, okra, potatoes, or legumes, and slightly pricier lamb, beef, or chicken options.

Since Penang’s seafood is peerless, a number of vendors will offer whole jumbo shrimps or other oceanic options. If you’re not sure where to start, simply point to a few dishes that catch your eye, then let the hawkers recommend a few others. Not all places offer roti, but should you spy the flaky flatbreads, add a few to sop up the extra gravy.

Nasi Lemak

Nasi lemak

While the rice in nasi kandar serves primarily as a vehicle for soaking up all that sauce, in nasi lemak, it’s the star of the show. The name loosely translates as “rich rice”—an apt description.

Here, the long grains are rinsed repeatedly, then simmered with coconut milk and pandan leaves until tender and fragrant. On occasion, butterfly pea flowers lend a striking blue hue. Often considered the national dish of Malaysia, nasi lemak is equally at home on tables during breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Nasi lemak

All nasi lemak starts with a molded dome of rice, but cooks can go in all sorts of different directions with the garnishes. Halved, hard-boiled eggs, peanuts, ikan bilis (fried, salted anchovies), cucumber slices, and spicy sambal are typical accompaniments, although some cooks may also add fried chicken wings, fried fish, or grilled fish cake.

Pasembur

Pasembur

Known as rojak mamak in other parts of Malaysia or Indian rojak in Singapore, pasembur is particularly associated with Penang. It’s not hard to see why this bright, crunchy salad with its bold combination of textures is a crowd-pleaser.

Shredded cucumbers, turnips, potatoes, and beansprouts typically form the base, which vendors top with fried squid, prawn fritters, octopus, tofu, fishcakes, crabs, or even jellyfish. A savory, nutty dressing binds it all together. Head to Gurney Drive to sample as many renditions of this dish as possible.

Oyster Omelet

Oyster omelet

Various iterations of oyster omelets can be found from Singapore to Bangkok to Taipei. Since the dish is Hokkien and Teochew in origin, it tends to make appearances wherever these communities settled down around Southeast Asia.

In Penang, this dish is known as oh chien and it’s an essential order for seafood-lovers. The combination of plump, briny oysters bound in a loose, eggy batter makes for superb eating, day or late at night. Rice flour or tapioca starch ensures that the oh chien picks up gorgeously lacy edges as soon as it comes in contact with the searing-hot griddle.

Oyster omelet

When properly made, oh chien should contain a satisfying mixture of wobbly, almost gooey center pieces and crispy bits, chopped up and tossed around the just-cooked bivalves.

Most hawkers serve it with a few scallions and plenty of hot sauce. Oysters are traditional, but plenty of hawkers will whip up renditions packed with mussels, prawns, squid, or other seafood.

Chee Cheong Fun

Chee cheong fun

Don’t let the name fool you—although chee cheong fun loosely translates as “pork intestine noodle” this dish contains no offal. Instead, it consists of fresh rice noodles rolled into balls and liberally soaked in a savory sauce. Once steamed, the noodle bundles have a satisfying chew.

Chee cheong fun draws on Cantonese culinary traditions, but cooks in Penang have very much made it their own. Hawkers here typically spoon on an umami-loaded sauce made with fermented red shrimp, as well as crispy fried shallots, and a sprinkling of sesame seeds or chopped peanuts.

Wantan Mee

Wantan mee

Every morning, vendors selling wantan mee set up shop on street corners all around George Town. These noodles, which are Cantonese in origin, appear all over Hong Kong, Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia.

Wantan mee

It’s hard to picture a much more soul-soothing way to start the day than a steaming bowl of egg noodles, emerald stalks of Chinese kale, slivers of char siu, and handmade pork wontons. Many of the food stalls have been in the same family for generations and which ones serve the best food in Penang is a constant source of friendly debate among locals.

Just as every New Yorker has their go-to bagel order, locals in Penang all have their preferred way to order wantan mee. Some opt for a ladle of bone broth, creating a wholesome soup, while many stick to “dry” noodles.

Hawkers here have their ratios down to an exact science, but it’s usually possible to ask for extra dumplings or pork.

Hokkien Prawn Mee

Hokkien prawn mee

This luxurious bowl of noodles takes full advantage of Penang’s stellar seafood. Giant, head-on shrimps sit swimming in a rich broth, alongside slices of pork shoulder or ribs, and egg noodles.

Dollops of chili jam or sambal add spice, while bean sprouts and fried shallots add a welcome crunch factor.

To up the ante even further, some cooks in Penang add on slices of fish cake or brittle pork cracklings. While you’ll find variations of Hokkien mee (noodles) all over Malaysia and Singapore, locals in Penang are particularly proud of theirs.

Every kopitiam and hawker stand has its own version and it’s well worth trying as many as possible.

Hokkien prawn mee

Much like wantan mee and other types of noodles, Hokkien prawn mee can be ordered “dry”, but this is one instance where you’re missing out if you skip the soup. To make this stock, cooks simmer whole shrimp heads and shells alongside a host of aromatics.

The result is a deep, rust-colored broth bursting with flavor and some of the best Penang food you’ll try.

Cendol

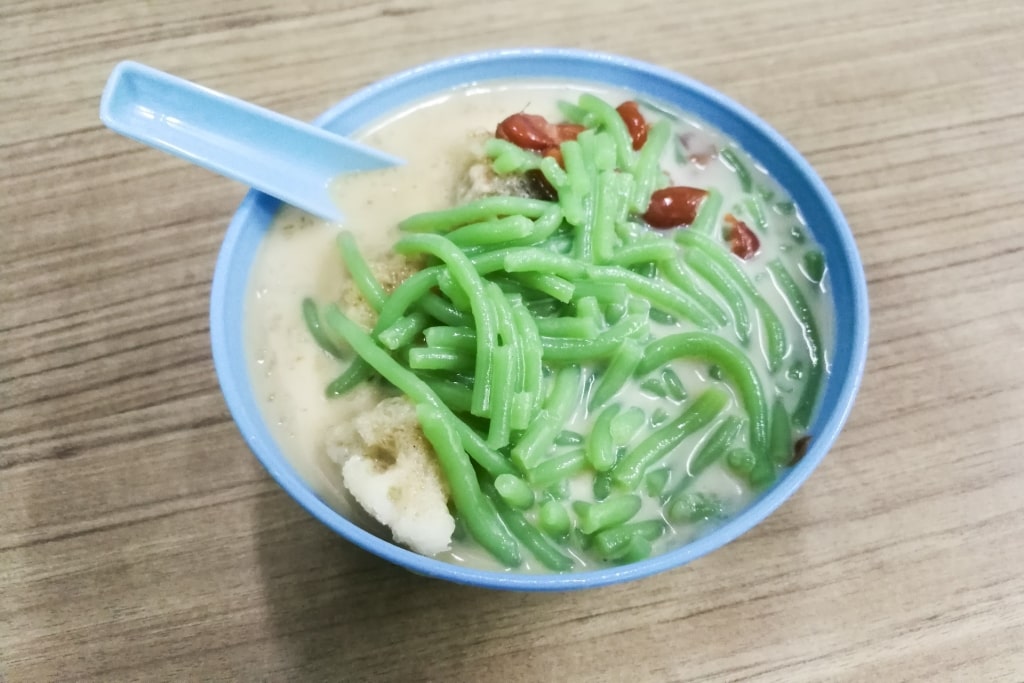

Cendol

On scorching days, nothing is as blissfully refreshing as an icy bowl of cendol. Consisting of elongated rice flour and sago jellies doused in coconut milk and palm sugar syrup, then sprinkled with shaved ice, this saccharine confection is the perfect way to beat the heat.

Pandan leaves, which have a subtly sweet fragrance reminiscent of pine and vanilla, give the jellies a vibrant green hue. Given the climate, it should be no surprise that variations of cendol exist all over Southeast Asia, although each country puts its own distinctive spin on the formula.

Thais call the dessert lot chong and typically serve it in a glass as a beverage, while Malaysians prefer it in a bowl.

Cendol

Although the basic components are the same, vendors around Penang regularly get creative with toppings. Jackfruit, diced mango, corn kernels, and sweetened red beans are all common additions. Gula melaka, a dark syrup made from palm sap with deep caramel undertones, is a particularly popular addition in Malaysia.

Cendol with durian

When durian is in season, it makes for a terrific topping. Yes, the spiky “King of Fruits” has a well-deserved reputation for being pungent, but Malaysian durians are also custardy and incredibly delicious when ripe.

Inspired to try some of the best food in Penang? Browse our cruises to Penang to plan a culinary adventure.